Design

Traditional timber framing is a very versatile medium both structurally and aesthetically, not only within the confines of the historical and regional variations, of which there are many, but also in an innovative and creative way. The framing tradition that we are part of is much like a living language that is as useful now as it was in the past. As such it can be used in novel ways to respond to modern needs and designs which push the boundaries beyond its historical forms. I can offer a frame design service backed by two decades of experience in all aspects of the process.

Traditional timber framing is a very versatile medium both structurally and aesthetically, not only within the confines of the historical and regional variations, of which there are many, but also in an innovative and creative way. The framing tradition that we are part of is much like a living language that is as useful now as it was in the past. As such it can be used in novel ways to respond to modern needs and designs which push the boundaries beyond its historical forms. I can offer a frame design service backed by two decades of experience in all aspects of the process.

The design of a frame affects not only its structural stability and its aesthetics, but also the way it integrates with the other elements of the build, how it fits with the clients needs, and its “buildability”, a very important factor which can also affect the cost of the frame significantly.

These variables must be dealt with principally by the architect and the framer, who usually produces the final frame design. To achieve greatest efficiency they should be discussed at an early stage to ensure a smooth transition from generalized concept to the ideal frame. It does sometimes happen that the design of the building is fairly advanced before the framer is approached. This is ok as well of course, and a frame design can usually be developed that fits the existing plans, but it’s usually either a bit of a shoe-horning process, or design changes mean the architects drawings have to be amended incurring extra costs and/or affecting the project programme. And the frame design itself may well not be what it could have been.

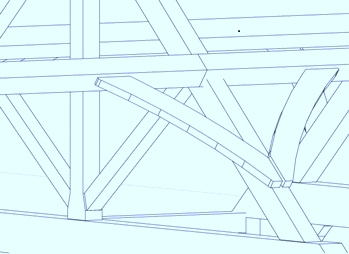

Efficient frame design The overall concepts underlying the build can affect the quality and cost of the frame in a number of ways: As with all other build elements the complexity of the build will have a disproportionate effect on the cost. It's not so much things like unusual angles or changes in floor level, with a fram e many of these kinds of things can be quite easily incorporated. Bearing in mind that oak frames are easiest to build when they are made up of two dimensional elements like cross frames, roof frames or wall frames (see right), the most important thing is to try to simplify the plan view of the frame into as few of these as possible.

e many of these kinds of things can be quite easily incorporated. Bearing in mind that oak frames are easiest to build when they are made up of two dimensional elements like cross frames, roof frames or wall frames (see right), the most important thing is to try to simplify the plan view of the frame into as few of these as possible.

A simple grid pattern with as few nodes as possible will always be the most efficient to frame. This is because the actual framing process in the workshop involves the laying out of each of the elevations in the horizontal plane over the framing floor, and a layout that has twice as much timber, and twice as many joints in it, takes much less than twice the time to frame up. Complexity in plan makes for many smaller layouts and therefore a costly frame. The fastest of all to frame is a simple grid as was used in almost all traditional buildings. It was not lack of i magination that constrained the master carpenters of the past to these simple geometric shapes, but a full understanding of the cost of breaking this particular mold. The other side of the coin is that, given an allowance for more framing time (and therefore more cost), irregular geometries, curved buildings, domes and ellipses can all be catered for.

magination that constrained the master carpenters of the past to these simple geometric shapes, but a full understanding of the cost of breaking this particular mold. The other side of the coin is that, given an allowance for more framing time (and therefore more cost), irregular geometries, curved buildings, domes and ellipses can all be catered for.

The cost of an oak frame is largely in the joinery. This means that if you increase the size of a house dimensionally, but retain the same frame design, it will not cost much more relative to the increase in floor area. So bigger frames are relatively cheaper.

Another issue worth addressing is the tendency to double up on structure. Oak frames can be designed to carry all the loadings that a building needs to resist, so the other elements of the build need not fulfill this functi on and can be limited to their other functions, for example secondary softwood framing simply carrying the insulation and/or cladding. The fashion at this time is for the timbers to be within the living space, visible on three or four sides, but the posts and plates can be pushed back,fully or part way, into the wall build to help reduce the doubling up of structure even further.

on and can be limited to their other functions, for example secondary softwood framing simply carrying the insulation and/or cladding. The fashion at this time is for the timbers to be within the living space, visible on three or four sides, but the posts and plates can be pushed back,fully or part way, into the wall build to help reduce the doubling up of structure even further.

The framers contribution When I design a frame my thoughts are principally on the structural strength and stability of the frame. I am not an engineer, but I know enough about the subject in relation to green oak framing, and I have enough experience of designing and building frames, to come up with something which will usually pass the engineers checks with small amendments or none at all.

Why only usually? Because the design and dimensioning of a frame is a balancing act between its strength and its cost. The frame designer as well as designing a strong frame must try to design a frame that is not wasteful, with unnecessarily large timbers or more of them than are really needed. So I am always trying to achieve the design remit in the most economical way possible.

The next ball in this juggling act is the aesthetic requirements of client and architect which  may clash with the structural element. Problems arise which need to be resolved thus requiring greater creativity and knowledge in the designer.

may clash with the structural element. Problems arise which need to be resolved thus requiring greater creativity and knowledge in the designer.

I also have to think about how the joinery is going to work and quite often actually draw out complex junctions to ensure the feasibility of them with regard to section sizes, loadings & forces and of course shrinkage.

With all this to think about it is very useful to have a large collection of traditional forms to fall back on, whose behaviour under load is well understood, and where the joinery details are known in advance. This ensures a degree of certainty about the results of the engineering checks and the buildability of the frame, which in turn mean speed, efficiency and no unexpected problems or other surprises. In the end, to the client these certainties mean a greater chance of hitting programme targets and most likely a cheaper price. This is why the tendency of the framer, like any tradesman, is to stick to what he/she knows best, thus avoiding possible pitfalls and therefore remaining competitive.

What I have said above should not be taken to mean that the unusual is impossible. Far from it, as I said at the top of the page, traditional framing is well suited to being developed in new directions, and I mysel f relish a bit of problem solving. I have been asked to push framing to the limit many times over the last two decades and have always enjoyed the challenge. But the new should be approached with caution and with careful consideration if we are to avoid disaster, and it is inevitable that it may be a little slower than the tried and tested way. However with this cautious approach and a really sound understanding of the way a green oak frame actually works structurally, both of which are things I believe I can bring to the table, much can be achieved.

f relish a bit of problem solving. I have been asked to push framing to the limit many times over the last two decades and have always enjoyed the challenge. But the new should be approached with caution and with careful consideration if we are to avoid disaster, and it is inevitable that it may be a little slower than the tried and tested way. However with this cautious approach and a really sound understanding of the way a green oak frame actually works structurally, both of which are things I believe I can bring to the table, much can be achieved.

Interface details: It

is not always simple to marry green oak frames with modern building

materials etc., therefore I will work in an advisory role with the architect

and the builder to ensure the frame element of a project dovetails seamlessly with the

rest of the build.  However

I am not usually responsible for the actual working drawings of the

interface between the frame and the rest of the building. If the

architect has not been engaged for RIBA work stage E "Technical Design",

which would usually cover this, then someone else will have to deal

with this element of the building design, possibly the builder or the

client themselves if they have experience in this field.

However

I am not usually responsible for the actual working drawings of the

interface between the frame and the rest of the building. If the

architect has not been engaged for RIBA work stage E "Technical Design",

which would usually cover this, then someone else will have to deal

with this element of the building design, possibly the builder or the

client themselves if they have experience in this field.

Drawings: At

the enquiry stage I usually produce a concept design based on planning

or warrant drawings and maybe a couple of telephone conversations with

client and architect. The concept sketches are usually very simple

overmarked copies of the architects drawings ("section thro' kitchen" right), annotated as necessary and

backed by a full list of the timbers and their sizes. Sometimes a proposal sketch is necess ary for which I usually do an annotated perspective drawing ("Wright sunroom" right). I can also supply

a sketchup model of the concept, however I try to avoid this if I can

because if I was to do it for every enquiry it would tend to push up

prices. In the last year or two it has become much more common for

companies to send out 3D models with their estimates, which tends to force everyone else to do the same in case they should look less

impressive, but I am trying to resist following down this road since I'm

not sure it is really necessary in most cases, and it is quite time consuming. I would rather

supply a 3D model only if it is requested or if it is necessary for some specific reason.

ary for which I usually do an annotated perspective drawing ("Wright sunroom" right). I can also supply

a sketchup model of the concept, however I try to avoid this if I can

because if I was to do it for every enquiry it would tend to push up

prices. In the last year or two it has become much more common for

companies to send out 3D models with their estimates, which tends to force everyone else to do the same in case they should look less

impressive, but I am trying to resist following down this road since I'm

not sure it is really necessary in most cases, and it is quite time consuming. I would rather

supply a 3D model only if it is requested or if it is necessary for some specific reason.

Subsequently, from

the information provided by the client or the architect; drawings,

dimensio ns, wall and roof buildups etc.I will usually produce a set of 2D

workshop drawings which will provide all the information regarding the

design of the frame (right). This is usually in a hand drawn on paper format but

can be supplied in 2D CAD format if requested. Once the client and architect have commented on the

design a second iteration is produced which will be the construction

drawings.

ns, wall and roof buildups etc.I will usually produce a set of 2D

workshop drawings which will provide all the information regarding the

design of the frame (right). This is usually in a hand drawn on paper format but

can be supplied in 2D CAD format if requested. Once the client and architect have commented on the

design a second iteration is produced which will be the construction

drawings.

J. Rose Carpentry